Passion, preparation and partnerships are some of the keys to successfully obtaining grant funding, according to injury and violence prevention researchers who shared advice during a pre-APHA 2022 discussion in Boston.

The Saturday workshop, “Increasing Diversity in Scholarship in Injury and Violence Prevention,” started with moderator Arlene Greenspan, associate director for science at the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, outlining the center’s research priorities.

The center focuses on addressing three urgent threats — adverse childhood experiences, overdose and suicide — as well as preventing injury and violence. That now includes research on gun violence and firearm injury prevention, which had not been federally funded for more than 20 years.

“It’s an area that’s long been neglected, and it’s really exciting to see the new research projects from our extramural colleagues,” Greenspan said. “Our work in firearm injuries spans all aspects of firearm injuries. We are interested in research on homicide, assault, suicide, as well as unintentional injuries.”

Greenspan also said the center is now intentionally focusing on health equity in each of its research priorities.

“While we have always included some aspects of looking at disparities, we have not previously taken a systematic and intentional approach to health equity. (We are) not only focusing on identifying disparities, but examining the underlying role of social and structural determinants of health in prevention, including issues such as racism.”

After reviewing descriptions and eligibility criteria in funding opportunity notices, Shabbar Ranapurwala, assistant professor at University of North Carolina, highly recommended reaching out to the program officer — and doing so early in the process. Write down and share your specific aims with the program officer, said Ranapurwala, who researches opioid overdoses, suicide and intimate partner violence.

“They will be able to tell you if it’s in line with what they’re trying to fund,” he said. “The more you can align your research with what the agency’s wanting to fund, the better you probably are of getting funded — even sometimes if your score is not as high as everybody else’s.”

It also means you won’t be wasting your or their time by writing and submitting a grant that is not aligned with the funder’s aims.

Donna Barnes, emeritus professor at Howard University, cautioned researchers not to hire someone to write their grant proposals. As a peer reviewer, she could always tell when that was the case.

“There was no passion; there was no character in the grant. It just sounded like rhetoric, and I was bored as I was reading it and thought, ‘What are they trying to do? I’m not sure,’” she said. “Put all the passion you can in that grant so that the reviewer can feel it.”

Barnes said she struggled to get federal research grants funded for her primary research focus of why suicide rates were increasing among people of color. Federal research grants tend to call for large population numbers, which her focus area didn’t have. So, she did some of the research on her own — examining death certificates at the coroner’s office – before focusing on training and program grants, which were funded.

More underrepresented minorities need to volunteer to become peer reviewers, she said. Diversifying the peer reviewer pool will help improve understanding of a researcher’s aims, she said. Greenspan agreed, saying that is a priority at the CDC center. And, even if someone thinks they are too junior of a researcher, they can apply and may be able to sit on a review panel, which provides valuable education of the process, she said.

Developing relationships with potential research partners is important, including with those who might not agree with your methods, said Sabrina Arredondo Mattson, senior research associate at the Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence at University of Colorado Boulder. In her research, partners have included members of the firearms community, who serve as advisors, helping to ensure consistent language and language that would resonate with the community.

Investigators also need to include senior researchers in their project. The challenges of working with outside researchers can include missed deadlines and the cost of hiring them, Arredondo Mattson said. She cautioned that some partners won’t be in line with your approach, so you will need to work hard over time to find trusted collaborators.

Senior researcher Kermit Crawford, associate professor at Boston University School of Medicine whose research has focused on mass trauma, shared how mentorship and training helped him as junior researcher.

A research career is “not like playing classical music (where) you play it just like the song that’s on the page. It’s more like playing jazz; you’re playing rhythm pattern, melody, chord structure, and you have to find your own way to get through that,” he said.

Crawford said the first federal grant application he submitted wasn’t even scored. After he finished his “pity party,” he volunteered to review grants to learn how to improve his. “That made so much difference — with the support I got from mentorship, sponsorship and the coaching — in my success.” After a period of peer reviewing, his next 12 grant applications were funded.

Each person’s course will be different and include failures.

“Your passion’s going to have to see you through,” Crawford said. “There will be some long, lonely nights, but there are other people out there who are interested in doing the same things you’re doing. And, you’ll find them because they’re looking for you too.”

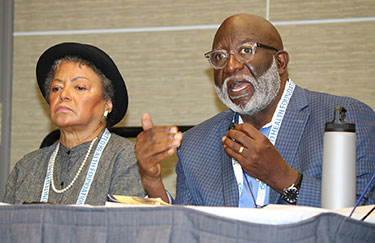

Photo: Donna Barnes and Kermit Crawford. Photo courtesy Michele Late, The Nation's Health.