Deaths among middle-aged adults in the U.S. have increased substantially this century, reversing decades of progress.

Deaths among middle-aged adults in the U.S. have increased substantially this century, reversing decades of progress.

Among the primary drivers of the deaths are drug poisonings, alcohol-related causes, suicide and cardiometabolic diseases, which include conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney failure. The findings were published in a 500-page, 2021 consensus study report on “High and Rising Mortality Rates Among Working-Age Adults,” from the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine.

At a Tuesday APHA 2021 session on “Rising Midlife Mortality Rates in the United States: Why Are Some Populations and Places More Affected?”, several members of the interdisciplinary committee that wrote the report discussed their findings. The authors said they wanted to go beyond the three drivers of deaths to get at their root causes and figure out why so many Americans are now dying in midlife.

Life expectancy progress in the U.S. stalled in 2010 and then fell between 2014 and 2017 — “the longest sustained decline in a century,” said Committee Chair Kathleen Mullan Harris, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The committee examined mortality trends from 1990 through 2017 for people ages 25-64 by age, sex, race and ethnicity, and geography. Two notes: the report was concluded before the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore doesn’t address those mortality rates; and the available data did not allow the committee to examine mortality trends among Asians or Native Americans.

Since 2010, for all age groups, death rates either leveled off or increased. Three groups had higher all-cause mortality rates in 2017 than they did 27 years before: white males ages 25-44, white females ages 25-44 and white females ages 45-54.

Drug poisonings linked to the biggest rise in deaths

Drug poisonings were the largest contributor to all-cause mortality, Darrell Gaskin, professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told session attendees. They increased in every demographic group studied and in every state, especially in Appalachia and parts of the Northeast. The largest increases were among white males ages 25-44, urban residents, those with lower education levels, and urban Black men ages 55-64.

The committee pointed to two themes underlying the increases: increased availability and increased vulnerability. The rise in drug poisoning deaths is connected to the emergence of opioids being prescribed for noncancer pain, coupled with opioid overprescribing and regulatory failures, Gaskin said.

“The pharmaceutical industry had convinced the regulators that addiction would not be a problem with this pain treatment,” he said. “Unfortunately, the technology they used to develop these opioid treatments was easily defeated by users.” (Opioid pills’ time-release element is easily bypassed when the drug is crushed, snorted or injected.)

“As a result, we see massive increases in the use of opioid prescribing and subsequent rise in prescription opioid misuse, addiction and overdose,” Gaskin said.

The second wave of the opioid crisis began as policymakers and regulators placed restrictions on opioid prescribing, which caused many users to transition to heroin and fentanyl. The third wave of the crisis began when illegal drug suppliers began to mix other drugs with fentanyl, which was less expensive but more potent. Overdoses spiked, and in 2010, fentanyl deaths surpassed heroin deaths.

Despite all this, the problem is bigger than the opioid crisis, Gaskin said. Deaths from cocaine and methamphetamine use also increased in the 2010s. In addition, there’s been a rise in alcohol use linked to price decreases, increased availability, weakening of government oversight and marketing of flavored alcoholic beverages, he said.

Vulnerability paves the way for increased drug use, suicide

Adults in the U.S. may be dealing with physical pain, mental illness, adverse childhood experiences, as well as despair, hopelessness, sadness and worry. Furthermore, economic and social change in the U.S. — such as prolonged unemployment, weak safety net programs, housing foreclosures and a growing socioeconomic inequality — can increase an individual’s vulnerability, according to researchers.

Vulnerability also plays a role in the next driver of all-mortality deaths: suicide. Increases in suicide mortality were mostly limited to white adults in all age groups, especially among males and in rural areas. However, beginning in about 2012, suicide rates among Black and Hispanic men ages 25-44 also began to increase. (The suicide data in the report does not include those from drug overdoses; those are included in the drug poisoning data.)

Suicide variability was small among the states in 1990, but by 2017, there was a lot more variability, with particular increases in West Virginia, the Dakotas, Wyoming, Montana, Alaska and Oklahoma. As with drug poisonings, economic trends in the U.S. likely contributed to the increase in suicide, said Irma Elo, professor at University of Pennsylvania.

More research still needed to understand why deaths have spiked

The third driver of all-cause mortality is cardiometabolic diseases. Over the 27 years studied, there was a decrease in deaths from HIV/AIDS and several types of cancer, which improved mortality rates for most demographic groups. However, mortality rates increased in several groups due to hypertensive disease, ischemic heart disease, and endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases.

The committee provided several policy recommendations in the areas of medical science and health care delivery, social and economic policy, and public health.

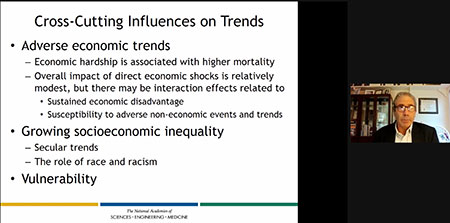

“The policy responses need to be multi-level, and they need to think about not only the proximal causes of death…but the causes of the causes that operate upstream that make those communities and individuals more vulnerable to the social determinants of health and people (using) unhealthy coping behaviors,” said Steven Woolf, professor at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“There are multiple drivers at multiple levels; we can’t blame all of this on opioids or obesity,” Woolf told session attendees. “This trend in working-age increased mortality is a uniquely American phenomenon. It’s not happening in other high-income countries, so there’s a real need for cross-national research to understand what is it about America that is responsible for this particular phenomenon?”

Photo of presenter Steven Woolf by Melanie Padgett Powers