Science communicators shared how they use social media to educate people about science and debunk conspiracy theories during a panel at yesterday’s virtual National Student Meeting.

The session, “The Importance of Social Media in Public Health Messaging: Adapting to This Generation’s Methods of Communication,” provided tips, success stories, case studies and advice on how to dive into translating science and public health messages for people online.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, infectious disease epidemiologist Jessica Malaty Rivera, a research fellow at the Innovation & Digital Health Accelerator at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, said she primarily has used Instagram Stories to share public health and science messages with her 359,000 followers.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, infectious disease epidemiologist Jessica Malaty Rivera, a research fellow at the Innovation & Digital Health Accelerator at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, said she primarily has used Instagram Stories to share public health and science messages with her 359,000 followers.

Rivera also served as the science communication lead for the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic, after she reached out to the journalists who started the project and offered to help explain the data.

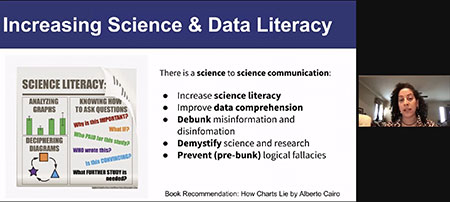

“That’s what led me to probably the most meaningful work in all of my disease surveillance and science communication work,” she told attendees at the meeting, which was hosted by APHA’s Student Assembly. “Our primary goal in that was to increase the general population’s science and data literacy.”

Rivera wants to demystify science and research. “For so long, science has been a very inaccessible field for a lot of people based on income, education, race and ethnicity. I like to break down those stereotypes, break down those barriers, and help elevate the voices of people who may not look like what you would assume is a scientist, to invite people into this process.”

Rivera said she feels strongly that there needs to be science-to-science communication, rather than nonscientific people looking for social media fame by trying to explain science without the proper knowledge.

Rivera said she feels strongly that there needs to be science-to-science communication, rather than nonscientific people looking for social media fame by trying to explain science without the proper knowledge.

“There’s actually a very technical process of understanding how to explain science, with the goal always being to increase science literacy, improve data comprehension, and not to primarily just debunk misinformation and disinformation,” she said. “There’s a discernment that’s required to understand what actually is worth the debunk.”

Instead, science communicators can “pre-bunk,” or prevent the logical fallacy trap people often fall into when they’re reading headlines and infographics that lack context or proper explanation. The COVID Tracking Project, as well as Rivera personally, does this by frontloading the good data.

“If you perceive science communication as just debunking, you’ll be playing whack-a-mole until you die,” she said.

The necessary knowledge to succeed in science communication makes public health professionals good candidates to become online science communicators. Rivera also noted areas within the practice of online science communication that need improving, such as empathy, inclusivity (language, age, sexual orientation), cultural competency (including recognizing medical mistrust) and true accessibility.

She shared the below best practices for science communicators to follow:

- Know when to say “I don’t know.” Rivera often says “time and data will tell.”

- Seek consensus and reproducibility.

- Remember audiences are not monolithic.

- Use “truth sandwiches,” meaning instead of focusing on the misinformation, start and end with the truth and, in the middle, explain what is wrong with the misinformation.

- Discern what needs to be debunked.

- Be strategically repetitive. A message often needs to be repeated multiple times before it gets through.

- Share personal experiences.

- Collaborate with other experts.

Anyone interested in communicating science effectively online, Rivera said, should know that “success is not always going viral but having meaningful changes from one person to one person.”

Top photo from Rivera's Instagram post about the importance of getting a flu shot. Second photo by Melanie Padgett Powers