Since 1951, officers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Epidemic Intelligence Service have been on the ground in major disease outbreaks, from polio and smallpox to Zika virus and COVID-19, conducting vital work that saves lives. But that almost came to an abrupt end this month.

Members of the much-lauded training program were initially told they were being axed as part of ongoing Trump administration budget cuts, but following uproar, the action was reversed, according to new reports. Many others at CDC were not as fortunate, however, with a reported 1,400 employees fired agency-wide.

Fears remain high that Trump administration actions could impact the EIS program's ability to respond to disease outbreaks, with the future of the program's next class of trainees unknown.

The Nation’s Health spoke to Denis Nash, PhD, MPH, a distinguished professor of epidemiology at City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health who served as an EIS officer in 1999, about the importance of the program.

What would it mean to public health disease response if there were no EIS?

There wouldn't be that cadre of staff that gets on the ground rapidly and as quickly as they are.

The other thing is that, since it's a training and capacity building program, the people that go through it represent the next generation of public health. So without it, there would not be the experiential training and capacity building that replaces each generation of leadership in public health all around the U.S., not just at CDC, and in many places around the globe.

A significant proportion, maybe 10 or 15% of my class, were people that came from overseas. And many of them went back after afterward. And we also had people from different branches of the military, people from the Army, Air Force, etc.

And each time those folks would go back to their original stations, (they were) bringing the capacity and experiences that EIS taught them.

What are the financial implications for poor outbreak response?

Missed outbreaks cost a lot in general. They cost society and every time you have an outbreak, it usually represents some breakdown in the public health system.

Think about the foodborne disease outbreaks, where the root has to be recalled or plants need to be shut down — the earlier you can detect these things, the less of an economic impact they'll have.

If you think about something like the bird flu situation right now, obviously that's costing everybody a lot of money. There's the dairy farmers whose milk production has gone down as a result of their cows being infected. There's the cost of eggs that's skyrocketing because of all of the cullings of infected bird flocks that have happened. These are all really expensive things. And we always say, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

What would the long-term effects be if there were no future generations of EIS officers?

It's going to mean that we can't respond to as many outbreaks. We'll miss outbreaks or we'll be much slower to respond to them. All this translates into worse health outcomes and avoidable death.

Obviously, cuts to EIS would be devastating. But the cuts that are happening to other staff at CDC are equally devastating and all that is cutting away at our public health infrastructure.

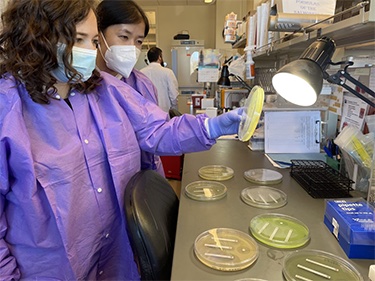

Caption: EIS officers examine antimicrobial resistance patterns in bacterial isolates at the Connecticut State Public Health Laboratory in 2022 following a multistate disease outbreak. (Photo by Meghan Maloney, courtesy CDC Public Health Image Library)